Impact of COVID-19 on Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons in the State of New Jersey – Preliminary Findings

Dr. Pooja Gangwani, Dr. Gregg A. Jacob, Dr. Shahid R. Aziz

Introduction

The current pandemic caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has threatened global healthcare systems. At the time of this writing (June 2020), the Johns Hopkins COVID-19 case tracker1 reports that COVID-19 has sickened more than 13,360,401 people and has taken over 579,546 lives around the world. The unfortunate reality is that these numbers will increase in the coming weeks. In the United States, more than 3,434,636 people have tested positive for COVID-19, and the death toll has surpassed 136,493. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME)2 projects nearly 224,089 deaths by November 1, 2020.

The first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the United States was reported in Washington state on January 21, 20203. Since then, the virus has spread to every state. Although New York City has been the epicenter of this deadly disease, New Jersey has the second highest number of confirmed cases and deaths,1 not only due to its proximity to New York City, but also due to its population density4 and presence of the three busiest international airports in the NY/NJ region.4

The death rate from COVID-19 in New Jersey is around 175 per 100,000 people, the highest in the nation.5 The pandemic arrived in New Jersey in late February 2020, with the first confirmed case on March 4, 2020.3 From mid-March 2020 through May 25, 2020, in order to maximize intensive care unit beds and ventilators, increase overall hospital bed capacity, and preserve the supply of personal protective equipment (PPE), all hospitals in New Jersey postponed elective surgeries, permitting emergent cases only.On March 21, 2020, the New Jersey State Board of Dentistry issued a directive advising all New Jersey dentists to cancel all “elective, non-essential, or routine service until at least April 20, 2020” to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Two days later, on March 23, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy “issued Executive Order No. 109, which suspended all elective surgeries performed on adults, whether medical or dental, and all elective invasive procedures performed on adults, whether medical or dental, effective March 27, 2020, at 5:00 p.m.”6

The purpose of this study was to investigate the impact of COVID-19 on New Jersey oral and maxillofacial surgeons via two surveys conducted in April and May, respectively. The goal of the April survey was to examine the surgeons’ preparedness (or lack thereof) and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the specialty of oral and maxillofacial surgery in New Jersey. The intent of the May survey was to assess the infection rate amongst oral and maxillofacial surgeons and health care workers, including both surgeons and staff (OMSHCW), impact on practice since the April survey, and concerns related to re-opening.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the St. Joseph’s University Medical Center’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) as an IRB Exempt Study (EX#2020-26). The leadership of the New Jersey Society of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (NJSOMS) felt compelled to acquire a deeper understanding of how its membership was responding to Executive Order 109. As such, an initial self-administered, web-based (Survey Monkey) anonymous survey was sent to the membership via email on April 1, 2020 (View Survey), and a second follow-up survey was sent out on May 1, 2020 (View Survey). A cover letter was attached at the beginning of each survey. Both surveys were official correspondence of the NJSOMS.

The surveys were kept open for ten days after their initial administration. To ensure participation, a reminder email was sent a week later after the initial email. The April survey included 20 questions designed to gather information about respondents’ COVID-19 related awareness, preparedness, attitudes, behaviors and change in practices. To assess the infection rate and concerns pertaining to re-opening, a follow-up anonymous survey was administered to the same group on May 1, 2020. It consisted of 27 questions. Data were anonymously collected and analyzed through an online survey tool. Questions pertaining to the purpose of the study were included for the analysis.

Results

April Survey

Of 232 members of the NJSOMS, 125 answered the survey, accounting for a 53.88% response rate. Of the oral and maxillofacial surgeons who responded (N=118), 83.05% (N=98) identified as full-time private practitioners, 2.54% (N=3) as practicing full-time in an academic setting, and 12.71% (N=15) as practicing part-time in an academic setting, and part-time in private practice.

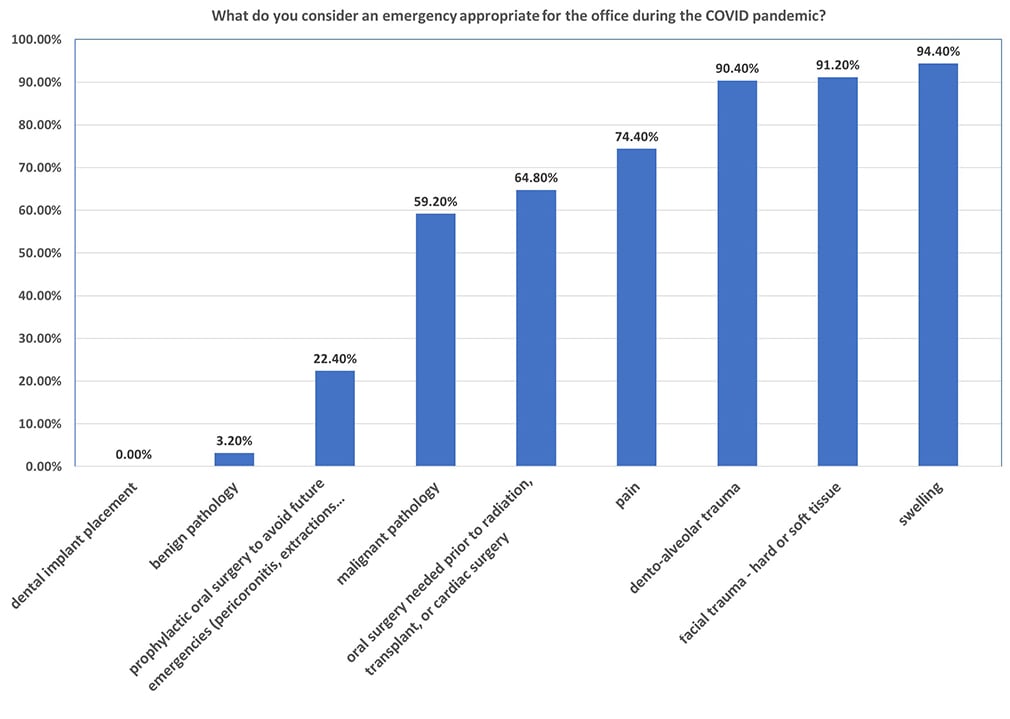

During the first three weeks of March, 28% (N=35) operated business as usual, 60% (N=75) were open for emergencies only, and 12% (N=15) of respondents had completely closed the office. When asked what qualified as emergencies, over 90% (N=113) of respondents identified swelling, dento-alveolar trauma, and facial trauma (hard and soft tissue) as indications to operate during the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 1). Figure 1: Bar graph representing which procedures were considered emergencies/appropriate for the office during the COVID-19 pandemic

Figure 1: Bar graph representing which procedures were considered emergencies/appropriate for the office during the COVID-19 pandemic

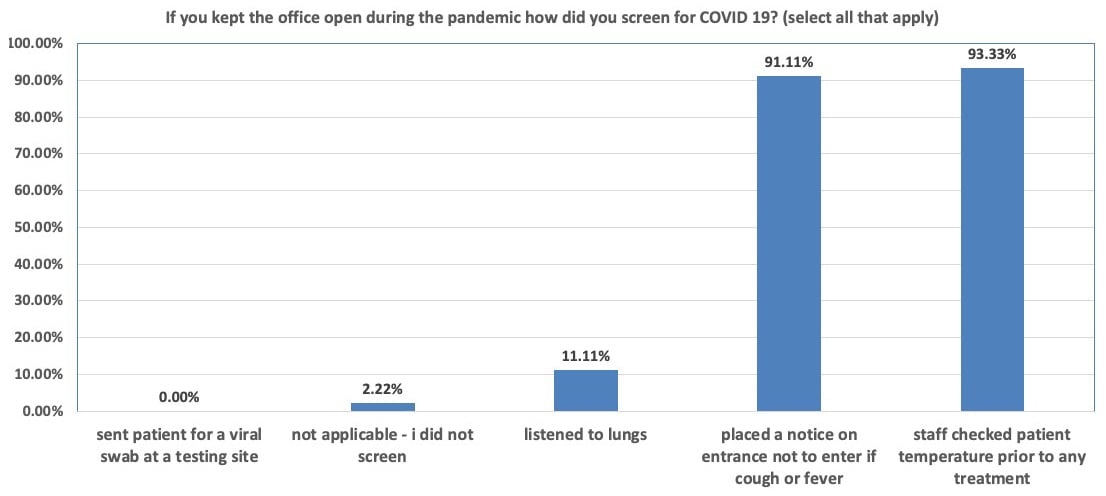

The limited stock of appropriate PPE was of primary concern for all health care providers. When asked about access to appropriate PPE, 74.40% (N=93) of respondents did not have N95 masks in the first three weeks of March. Of those who did have N95 masks (N=77), 92.21% (N=71) were reusing them. Of the 72% of respondents who did not have appropriate PPE, 58.89% (N=53 of 90) were willing to treat emergency patients during the pandemic. Of the surgeons who kept their offices open (N=90), COVID-19 screening was basic: over 90% (N=82) of them had their staff check patient’s temperature prior to any treatment and placed a notice on their entrance to not enter the office if experiencing symptoms such as cough or fever (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Bar graph representing screening methods employed by survey respondents during the COVID-19 pandemic

To care for patients, health care professionals increasingly relied on tele-health. 33.06% (N=41) of our respondents (N=124) utilized telemedicine to treat their patients. Traditional telephone calls (73.91%, N=34), FaceTime (34.78%, N=16) and Zoom (19.57%, N=9) were the three most commonly used platforms. 68.29% (N=84) had to furlough their staff, and majority of them were able to help their staff with obtaining unemployment benefits.

May Survey

Of 232 members of the NJSOMS, 141 answered the survey, accounting for a 60.78% response rate. Between March 20 and April 20, 83.69% (N=118) of respondents were open for emergencies. Of those open for emergencies, 48.33% (N=58) of the surgeons saw multiple patients per day, 25% (N=30) saw patients one to two times per week, 14.17% (N=17) every other day, and 7.50% (N=9) less than once a week. A small percentage (5%, N=6) of managed patients once daily. Most of the respondents felt that the emergencies handled in their offices were legitimate, including infections, facial trauma, and dento-alveolar trauma. When asked about hospital cases, 12.77% (N=18) of respondents performed procedures in the operating room between March 20 and April 20, mainly treating cases of infection and trauma.

We wanted to know the infection rate in the OMFS community and asked our membership if they had tested positive for COVID-19. Of those who responded, 1.42% (N=2) had tested positive for COVID-19, and an additional 12.23% (N=17) believed that they were ill with COVID-19 symptoms but had not been tested. 14.49% (N=20) of respondents stated that member(s) of their staff had tested positive for COVID-19. Two of these 20 respondents each had three of their staff members tested positive. The vast majority (88.46%, N=23 of 26) of those who tested positive were required to quarantine at home, followed by full recovery. A minority required an emergency room visit (7.69%, N=2 of 26) or hospital admission (3.85%, N=1 of 26). Of our respondents, all had successful outcomes at the time of the writing, with no fatalities.

Next, we inquired about preparedness for re-opening. We asked our membership questions about the availability of PPE, social distancing employment strategies, screening protocols, and office environment safety precautions. When allowed to return to normal practice, 59.29% (N=83) of respondents reported that they would have adequate PPE, 80.14% (N=113) would have enough surgical masks for their front desk staff, and 52.48% (N=74) would also be willing to provide surgical masks to their patients.

Upon re-opening, 94.33% (N=133) of the responding oral surgeons planned to have staff take temperatures of fellow staff and patients. In order to practice social distancing, 75.18% (N=106) of the respondents planned to have their patients wait in the car to be called in, and 24.82% (N=35) planned to employ social distancing in the waiting room.

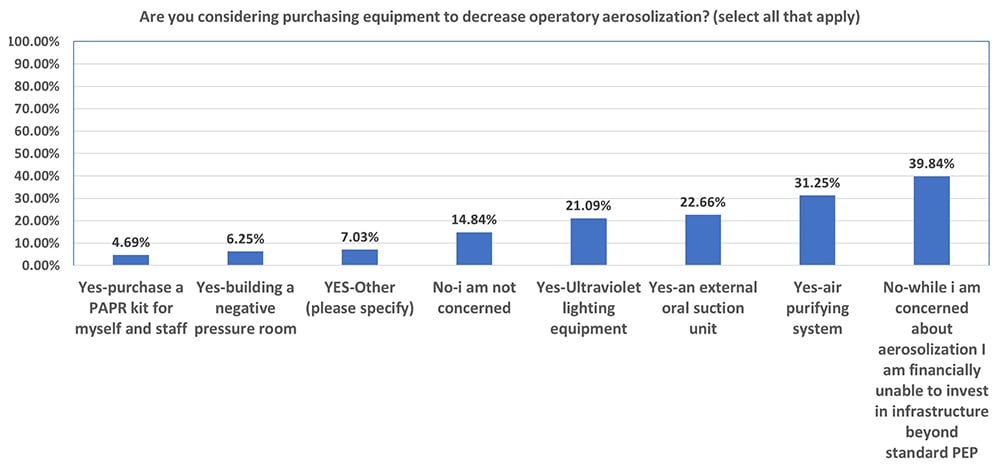

When asked about considering purchasing equipment (Figure 3) to decrease operatory aerosolization, 39.84% (N=51) of respondents voiced their financial inability to invest in infrastructure beyond standard PPE. 31.25% (N=40) and 22.66% (N=29) were considering purchasing an air purifying system and external oral suction units, respectively. 21.09% (N=27) expressed their interest in utilizing ultraviolet lighting equipment. 82.27% (N=116) of the respondents planned to space out their appointments to allow for the operatory air to settle and help clear out possible aerosols. 61.15% (N=85) of respondents were unsure at the time of answering the survey, and were awaiting AAOMS, ADA, or CDC recommendations regarding spacing out appointments.

Figure 3: Bar graph representing respondents’ intentions regarding purchasing of equipment to decrease operatory aerosolization

Discussion

PPE, Testing & Screening

Our results show that the vast majority of oral and maxillofacial surgeons (74.40%, N=93 of the respondents) in New Jersey did not have appropriate PPE (defined as N95 masks) in late February/early March. This reveals deficiencies in the current healthcare system with regards to pandemic preparedness and response capabilities. Over 90% of the respondents who were managing emergencies in their offices screened their patients based on clinical symptoms (cough or fever) and temperature checks. None of the respondents sent their patients for a nasopharyngeal swab at a testing site, presumably due to the lack of testing in the early weeks of March.

In mid-May 2020 (after the May survey closure), the CDC published basic dental office testing/screening guidelines:7

- Contact the patient the night prior to their appointment and screen for fever and/or cough. Advise patient to wear a mask to appointments, even if they are not experiencing fever or cough.

- The day of the appointment, check the patient’s temperature. Readings under 100.4°F are acceptable for treatment. Without any respiratory illness, this patient is presumed COVID-negative.

- If the patient has respiratory issues and/or a temperature greater than 100.4°F, do not allow the patient to enter office. Refer the patient to a local testing center, PCP, or urgent care center for testing.

- If the patient was COVID-positive in the past, but has completed 2 weeks of home isolation, they may be treated using standard procedures (temperature check, health screening, etc. as noted above). If the patient has self-isolated for less than two weeks, they should not be treated.

- COVID-positive patients are not to be treated in the office.

As of June 24, 2020, the CDC outlined the following guidelines for managing a medically necessary emergency procedure in a dental office, on a confirmed or suspected COVID-positive patient:8

- Provide treatment in a closed room.

- If possible, avoid aerosol-generating procedures.

- The following precautions must be taken if aerosol-generating procedures need to be performed:

-

- Providers in the room should wear an N95 or PAPR, eye protection, gown, and gloves.

- Limit the number of providers to only those who are essential for patient care.

- Perform the procedure in an airborne infection isolation room.

- Providers in the room should wear an N95 or PAPR, eye protection, gown, and gloves.

-

- Schedule the patient for the procedure at the end of the day.

- Avoid scheduling other patients at that time.

Infection Rates among surgeons and staff

Testing for COVID-19 is an ongoing process, and consequently the infection rate is constantly changing. Owing to the high-risk aerosol generating procedures they perform, oral and maxillofacial surgeons and surgical assistants are at increased risk for exposure to SARS-CoV-2.9 With the use of appropriate PPE (N95-type respirator masks, goggles, gowns, gloves) and screening protocol for our staff and patients on arrival, we can further mitigate the risk of introducing the virus into our practices.10

Impact on oral surgery practice

During the pandemic, the vast majority of the responding oral and maxillofacial surgeons were open for emergencies only. There was a significant reduction in non-emergency procedures performed. From March 20 through April 20, 97.16% (N=137) of the respondents did not perform elective surgery (implant placement). Surprisingly, there were a few members who did perform elective procedures during this time. Nonetheless, there was some confusion on what could be considered elective versus emergent or urgent care. For example, if sedating a patient to remove an infected/painful wisdom tooth, is it acceptable to remove other wisdom teeth to avoid additional sedation in the future? Another question pertained to immediate implant placement: is the procedure reasonable to perform (especially in an upper anterior tooth), given that the tooth had already been removed, the site was open, and placing the implant would allow the patient to function sooner and would increase efficiency of care?

The pandemic has also had a significant economic impact on oral and maxillofacial surgeons. The majority of NJSOMS members are private practice surgeons. As such, they are small business owners. Like other small business owners, many surgeons were forced to furlough their employees and apply for federal grant programs. While the government did provide a $3 trillion aid package (the CARES act), it was disappointing to see that only a small percentage of NJSOMS members who applied for the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) or Small Business Administration (SBA) loans initially received them — 82.27% (N=116) applied, but only 34.29% (N=48) had received loans by the time of our data collection. It should be noted, however, this information would only have included the initial round of funding for these programs. While many of our members did apply in a timely fashion, the lack of initial funding may have been due to an incomplete or inaccurate filing, confusion, lack of direction with filing, or simply a preference on the part of the banks towards larger borrowers. Since our data collection, a second round of funding has been released (beginning in late April 2020 and extending into May 2020). Fortunately, many of our members have since received the aid.

Re-opening

On May 13, 2020, the AAOMS released a detailed “Interim Reopening Protocol for the OMS Office.” It was re-assuring to see that the overwhelming majority of the responding oral surgeons planned to continue having staff take temperatures on fellow staff and patients. In order to practice social distancing, none planned to return to their pre-pandemic routine and instead, would continue taking exhaustive measures to mitigate the spread of the virus in offices and clinics. In terms of spacing out appointments, the majority of our members were unsure about their plans for the future, and were still awaiting further recommendations from governing bodies. In the last week of May 2020, the CDC released infection control guidelines for confirmed or presumed COVID-negative patients that stated: “To clean and disinfect the dental operatory after a patient without suspected or confirmed COVID-19, wait 15 minutes after completion of clinical care and exit of each patient, to begin to clean and disinfect room surfaces. This time will allow for droplets to sufficiently fall from the air after a dental procedure, and then be disinfected properly.”7 On June 17, 2020, the CDC removed these guidelines for COVID negative patients (tested negative or presumed negative).8

Tele-health and tele-education

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed unique challenges to the health care providers in delivering care to their patients. In the past two months, in order to stay connected with patients, tele-medicine has emerged as a valuable tool for health care providers across the country, and has offered a glimpse into the future. Our data shows that 33.06% of respondents utilized tele-health in the first three weeks of March. While virtual conferencing cannot replace in-person visits for surgeries, routine consultations can be completed through virtual appointments, minimizing the number of office visits. Virtual delivery of health care can be particularly useful for elderly patients, patients with multiple co-morbidities, patients who are immunocompromised, and even children. Along with tele-health, tele-education has also come into view. We can take this opportunity and re-imagine our learning, as this will allow us to connect with our specialty, and share experiences not only across the nation, but also across the globe. This will bring us all even closer, to achieve more together, in a short period of time.

Provider concerns

The following concerns have emerged upon surveying our membership:

- 52% (N=122) of respondents are concerned about aerosolization of viral particles during patient care.

- 84% (N=51) of respondents have expressed financial concerns regarding purchasing equipment beyond standard PPE.

Aerosolization of viral particles is a major concern for those surveyed. There are a few ways to truly protect oneself from aerosolization, including Powered Air Purifying Respirators (PAPR) and negative pressure rooms. PAPRs provide full protection from aerosolized particles as the respirators blow filtered air to the wearer, reducing aerosolization to 1/25th of the surrounding air. PAPRs present some significant issues for the practicing oral and maxillofacial surgeon, however, including equipment cost as well as decreased visual field while wearing the respirator.11

Another modality for guarding against aerosol spread is the negative pressure room. Negative pressure rooms use ventilation systems to generate negative pressure, allowing air to flow into the isolation room but not escape, thus protecting the rest of the office. Use of appropriate PPE is still essential while in the room. This modality requires physical modification to the treatment setting at significant cost, therefore it may not be fiscally feasible for private practice surgeons or a hospital-based clinic. Since the system requires exhaust to the outside of the building, existing treatment spaces may not support this modality.12 To date, we are not aware of any studies supporting the use of this in the OMFS setting to justify to cost and space modifications.

There are some less expensive options than negative pressure rooms, including Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) filtration systems and chairside extraoral dental suction devices which theoretically decrease aerosols. It appears that if offices are able to follow CDC guidelines — in particular, screening and proper PPE use, as well as maintaining the highest levels of infection control/disinfection protocols — offices should be protected from COVID-19 or any other virus until vaccines are available.

Limitations of this study

The data presented was obtained from a cross sectional survey, and thus it may be difficult to make causal inferences. Further, a response rate of a little over 50% leaves a possibility of a non-response bias. Lastly, the pandemic has been a dynamic process with rapidly changing evidence and science, and therefore it is difficult to use data that might even be a week old to glean true scientific evidence.

Conclusion

What is abundantly clear based on the data we have collected is that practicing New Jersey oral and maxillofacial surgeons have demonstrated superior clinical judgement and courage, and should continue to use appropriate diagnostic and clinical skills to minimize further spread of the novel coronavirus. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study performed on a state level to understand implications of COVID-19 on our specialty. Upon reflection, our national health care system was not prepared to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, and this has taught us valuable lessons. Dental professionals, in particular oral and maxillofacial surgeons, play an important role in managing patients with a variety of dental and maxillofacial issues. Providing national access to office-based dental care will help alleviate emergency room visits and hospital admissions, thus decreasing the overall burden on these facilities. As a specialty, we have to be prepared for the likelihood that the COVID-19 pandemic will continue, and may come back in a second wave – certainly until a reliable and effective vaccine is widely available.

__________

Dr. Pooja Gangwani

Assistant Professor, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, University of Rochester/Eastman Institute of Oral Health, Rochester, NY

Dr. Gregg A. Jacob

Private Practice, Northeast Facial & Oral Surgery Specialists, Florham Park, NJ; Clinical Assistant Professor, Division of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Department of Surgery, New York Presbyterian Hospital, Weill-Cornell Medical College, New York, NY; Vice President, New Jersey Society of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons

Dr. Shahid R. Aziz

Professor, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Rutgers School of Dental Medicine, Newark, NJ; President, New Jersey Society of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons

University of Rochester Medical Center

Strong Memorial Hospital

601 Elmwood Avenue, Box 705

Rochester, NY 14642

Email: pooja_gangwani@urmc.rochester.edu

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation https://covid19.healthdata.org/united-states-of-america.

- Coronavirus in New Jersey: A timeline of the outbreak https://www.nj.com/coronavirus/2020/03/coronavirus-in-new-jersey-a-timeline-of-the-outbreak.html.

- Here's why New Jersey and New York are the epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic https://www.nj.com/news/2020/03/heres-why-new-jersey-and-new-york-are-the-epicenter-of-the-coronavirus-pandemic.html.

- Death rates from coronavirus (COVID-19) in the United States (https://www.statista.com/statistics/1109011/coronavirus-covid19-death-rates-us-by-state/ - accessed May 25.

- COVID-19 updated notice to dental professionals https://www.njconsumeraffairs.gov/den/Documents/UPDATED-April-BoD-COVID-Alert.pdf accessed May 25, 2020.

- Guidance for Dental Settings https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/dental-settings.html accessed May 25, 2020.

- Guidance for Dental Settings assessed June 24, 2020 https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/dental-settings.html

- The New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/03/15/business/economy/coronavirus-worker-risk.html accessed May 25, 2020

- Menni C, Valdes AM, Freidin MB, et al. Real-time tracking of self-reported symptoms to predict potential COVID-19. Nature Medicine. 2020.

- Considerations for Optimizing the Supply of Powered Air-Purifying Respirators (PAPRs) https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/powered-air-purifying-respirators-strategy.html.

- Environmental Infection Control Guidelines https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/environmental/background/air.html#c5b.

This submission is included in the JADA+ COVID-19 monograph as a Clinical Observation entry and has not been peer reviewed.

Stock photo credits: rilueda/iStock/Getty Images Plus