ABSTRACT

Background

With COVID-19 infections escalating throughout the New York City (NYC) metropolitan area, NYU Dentistry, at the close of business on Friday, March 13, 2020, suspended all clinical operations. Only a small number of dental service sites in NYC, that met the stringent, infection-control guidelines necessitated by COVID-19, were able to remain open.

Description

Having anticipated that wide-spread suspension of clinical operations in the metropolitan area might become necessary during this public health crisis, NYU Dentistry had prepared a plan for an interim Dental Telehealth Service. This plan was quickly deployed and the service was fully operational by the start of business on Monday, March 17. A 24-hour Telehealth hotline was set-up and providers, NYU faculty (licensed dentists), from every specialty, were available for telehealth consultations. Patient inquiries were referred to the hotline. The number was also on NYU Dentistry’s website. Hotline callers were screened by trained telehealth agents who then routed those callers with a dental emergency or urgent care need to a provider for a Telehealth session.

Practical Implications

The NYU Dental Telehealth Service was developed to mitigate the impact of the widespread suspension of oral health services in the NYC metropolitan area during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly for those patients requiring urgent and emergency care. Once extensive infection control protocols had been implemented to safely resume delivery during the pandemic of clinical oral healthcare, this emergency Telehealth Service ended after several months of operation. The experience garnered, during its implementation during this public health crisis, regarding the use and acceptability of this service, supports the value of integrating Telehealth into the delivery of community-based oral healthcare services.

Introduction

The emergence in late 2019 of the new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has had a profound, global impact on virtually all industries and services. The transmission of the new coronavirus through respiratory droplets necessitated a host of unprecedented preventive measures to halt the spread of the virus in the population, including the shutting down of all non-essential businesses and services, sheltering in-place, social distancing and the widespread implementation of infection control procedures, e.g. population-wide wearing of masks, inconspicuous utilization of hand sanitizers and deep cleaning of public spaces and transportation facilities. The in-person delivery of oral healthcare has been profoundly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

For decades, dentistry has been at the forefront of research, development, implementation and utilization of personal protective equipment (PPE) and in strict infection control protocols. Nevertheless, in the early phase of the pandemic, COVID-19’s impact on the delivery of dental services has been far-reaching and severe. In many countries, including the US, all in-person non-essential dental services were effectively suspended for a period of time in the Spring of 2020. This drastic reduction in availability of direct patient care created the ideal disruption to catapult dental telehealth into the spotlight, as an alternative clinical service modality for an initial triage and a broad diagnostic assessment of patients’ needs. Extensive COVID-19 infection prevention and control guidance for dental healthcare facilities, have been issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)1 and American Dental Association (ADA)2.

Chronology of the initial phase of the pandemic in the US

The first case of COVID-19 in the US was confirmed in Washington State by the CDC on January 20, 20203. By late February, the NYC metropolitan region was experiencing a surge in COVID-19 cases and a rapidly rising number of deaths4 (see Table 1). In response to this growing public health crisis, on March 7th, Governor Cuomo declared a state of disaster emergency for the entire New York State5. A few days later, New Rochelle, a suburb of NYC, became the first geographical coronavirus hotspot in the country. On March 10th, this development precipitated Governor Cuomo to establish a one mile-radius “containment zone” in this community, implemented by the National Guard. As the escalation of COVID-19 infections continued to spread in NYC’s metropolitan area, further extraordinary safety measures were taken.

On March 15th, NYC mayor, Bill de Blasio, announced the closure of all NYC public schools as part of the efforts being enacted to slow the spread of the coronavirus. This action was followed by Governor Cuomo signing the “New York State on PAUSE” executive order on March 22nd6. This sweeping decree required the statewide closure of in-office personnel functions for non-essential businesses and banned non-essential gatherings of any size, for any reason. Emergency dental facilities, designated an essential health care operation, were permitted to remain open7.

The leadership of New York University College of Dentistry (NYU Dentistry) continued to monitor these rapidly changing events and, in combination with information from NYS, University and Federal guidelines, NYU Dentistry suspended on-site education, clinical operations and clinics at the close of business on March 13th, in an ongoing effort to safeguard the health of the NYU Dentistry community and its patients.

Addressing the need for urgent oral healthcare during suspension

of in-person dental care

The suspension of all clinical operations at NYU Dentistry left patients at risk for unmet oral health issues, particularly those requiring urgent and emergency care5. Prior to the suspension of clinical services, NYU Dentistry averaged more than 1,100 patient visits a day, delivering essential oral healthcare to the most multi-ethnic, multi-cultural patient population in the nation. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, NYU Dentistry’s clinical program provided direct patient care in DDS, and post-graduate (PG) programs, Monday–Thursday 8 a.m.– 8 p.m., and Friday 8 a.m.–5 p.m. Walk-in, urgent oral healthcare was available Monday–Saturday through NYU Dentistry’s Urgent Care Clinic, and the After Hours Emergency Care (AHEC) service.

With the suspension of clinical operations, and the state-wide, pandemic-generated lock-down, only a small number of emergency dental healthcare service sites in the NYC metropolitan area were currently open that met the stringent, infection-control guidelines necessitated by COVID-19. Although those facilities had access to PPE and appropriate infection control and air handling systems (including medical-grade air filters and proper air-flow), they were primarily housed in large hospital settings. In the early days of the pandemic, much of the public had strong reservations about seeking emergency dental care at hospital sites that were heavily inundated by very ill COVID-19 patients.

NYU Dental Telehealth Service. Anticipating that the COVID-19 pandemic could necessitate a suspension of clinical operations at some point, NYU Dentistry had prepared for this potential eventuality, convening a Patient-Centered Care Team. The team devised a plan for an emergency and urgent care dental telehealth service that could be quickly deployed should the pandemic impair access to and delivery of oral healthcare.

Consequently, within 24 hours of the school’s closure and indefinite suspension of all clinical care operations, the team’s emergency plan was implemented for a NYU Dentistry Dental Telehealth Service. This emergency program was in-place and fully operational by the start of business on March 17th. The program set-up a 24-hour hotline and volunteer providers from NYU faculty (all licensed dentists), from every dental specialty, were recruited for telehealth consultations. The Telehealth hotline number was posted on the College website, with notices of the suspension of clinical operations due to the COVID-19 pandemic. All patient inquiries were referred to the Telehealth hotline. The Telehealth Service operated Monday - Friday, 9 a.m. – 4 p.m. After hours, calls to the hotline went directly to Voice Mail. A recorded message advised callers that their call would be returned on the next business day.

The overall goal of this emergency Telehealth Service was to minimize patients’ in-person visits to hospitals and urgent care facilities during the period when NYU Dentistry’s clinical operations were suspended during the initial surge of COVID-19 cases in New York State. This emergent service was open to both patients of record and the general public. No fee was charged. Patients were advised to only call the service if they had an urgent or emergency dental issue. It was in operation from March 17th through August 31st. By the beginning of September, the phased re-opening of NYU Dentistry’s clinical operations was fully underway (see Table 1).

Overview of the Telehealth Service parameters. Telehealth agents, who were knowledgeable clinic staff, were the first line of triage in this telehealth service. Experienced in talking to stressed and anxious patients, they screened each call, obtaining details about the nature of the emergency (e.g. pain, swelling, bleeding, trauma), entering the data onto an electronic Patient Encounter Form (PEF), that also contained other pertinent information (e.g. demographics, pharmacy information, contact number). At the end of this screening call, patients were informed that a provider (e.g. licensed dentist on the NYU faculty) would call them back in about 15-20 minutes. The agent then electronically notified a provider, from the team of on-call NYU dental faculty. Once notified, the provider retrieved and reviewed the PEF, then contacted the patient, using Cisco Jabber8, an application that allows provider-patient communication via a computer phone line without the provider’s phone number being shared with the patient. The provider conducted the phone triage, administering advice and guidance on any immediate measures to be undertaken. A professional interpreting service was also available to participate on the call should a patient have limited English proficiency (LEP). Zoom was available for video conferencing, but was only used with patients of record, when they requested it. Patients were also able to upload a photo, which would be attached to the PEF, for the provider to review.

At each Telehealth session, the provider completed case notes using the SOAP format9 to document the session. Using this format, a standard organization of pertinent patient information and proposed treatment was ensured, as follows: Subjective observations the patient verbally expressed; Objective observations, factors one can measure, see or hear; Assessment of the problem, e.g. diagnosis or condition the patient has; and Plan of action, how the problem is going to be addressed. These case notes were later scanned in as an attachment to the patient’s EHR.

Using telehealth to diagnose and address urgent and emergency oral health issues

Telehealth Encounter. While telehealth facilitates patient access to clinical services, it also generates challenges for the provider. One of the more obvious challenges, was having to remotely conduct a patient assessment on an individual the provider had not seen before, while trying to achieve a complete and efficient clinical understanding of the nature of the patient’s problem, and the reason for the call. In NYC’s culturally polyglot environment, this type of clinical encounter can be difficult. Given these circumstances, it was important that the call began in a friendly, but professional manner. This reassured the patient, instilling confidence, generating engagement in the clinical discussion and helping to put a possibly agitated patient at ease. It was also important to use a guided conversation to listen carefully to what the patient was saying, summarizing the data collected, throughout the call to ensure a shared understanding, while taking care to not resort to unclear medical terms or jargon.

Assessment. The history component began with ascertaining the “chief complaint” with appropriate follow-up questions: When and where did the problem begin? What are the principal symptoms they are experiencing? Are they in pain (and if so, at what level)? Does hot or cold trigger hypersensitivity? Do they have any swelling or bleeding? Has that tooth had previous professional treatment? Do they have a fever, trouble chewing, swallowing or breathing? It was also important to ascertain the patient’s overall health status: Does the patient have any significant health conditions (i.e., diabetes, asthma, hypertension (HBP))? Do they have any allergies? Is the patient possibly pregnant? Are they taking any prescription medications? Are they allergic to any particular drug family? Are they taking any over-the-counter medications? Do they give any indication of having COVID-19? The guided conversation goal was to obtain a tentative diagnosis, a reason for these symptoms and to determine the best course of action given the current circumstances. In some instances, patients were able to provide more specific information that helped determine the cause, and treatment options, such as: “Root canal treatment was begun on #14 just before NYU Dentistry shut down. “Now the tooth hurts, again.” or “Tooth on the lower right had a big cavity and it was planned for extraction.”

Telehealth treatment options. Medication was an option that was considered. The caller’s local pharmacy proved to be an important treatment resource in these instances. No matter if the pain level was described as “moderate” or “severe” the goal was to always manage it with a non-opioid approach. The American Dental Association (ADA) suggests using NSAIDS alone or in combination with acetaminophen (Tylenol) for pain relief10. For odontogenic infections a wide spectrum antibiotic, such as Amoxicillin, is generally recommended. If another drug was sought, Clindamycin or Erythromycin may be appropriate11. However, when the caller had an emergency need that was unlikely to be relieved by medication, the patient was referred to their local hospital’s urgent or emergency care service. With very few exceptions, when patients had a dental professional quickly respond to their problem, someone who was prepared to listen, give advice, and offer some meaningful help or resource, they were exceedingly grateful. Most understood the limitations of trying “to treat” with the city under “lockdown.” There were more than a few “Bless you” given at the end of the Telehealth session. For those few patients who called back, after a week or so on home care or a regimen of antibiotics, and were concerned that their problem showed no improvement, the only alternative was to suggest a referral to their local hospital’s urgent or emergency care service.

Telehealth service: Call volume and service outcome

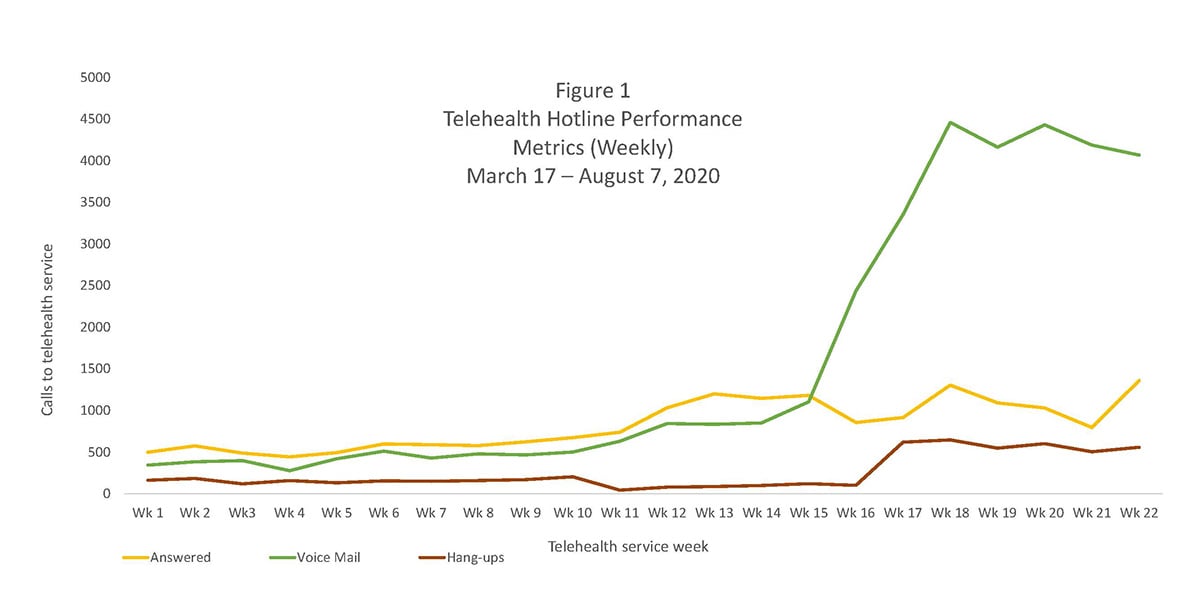

Telehealth hotline performance metrics. Total volume of calls to the hotline during the period that the Telehealth Service was operational are presented in Figure 1. Calls per week (7 days) are broken down by disposition: a) answered by a Telehealth agent; b) directed to voice mail (occurred when agents were on another call or the service was closed); and, c) abandoned calls (caller hung-up without leaving a message). Telehealth agents screened all hotline calls and returned all voice mail messages. Through the first 14 weeks of the Telehealth Service, the hotline received an average of 1,435 calls per week. NYU Dentistry’s phased re-opening of clinical services began on June 29th. That week (week 16, June 29th – July 5th), the hotline call volume almost quadrupled. This trend continued. Overall, in the last seven weeks that the Telehealth program continued (weeks 16-22, June 29th – August 16th), the call volume on the hotline averaged 5,435 calls per week. Many of these calls were likely for appointments or general information given the re-opening of NYU Dentistry’s clinical operations. However, as discussed below, the number of calls that were routed to a provider during this period increased, as well.

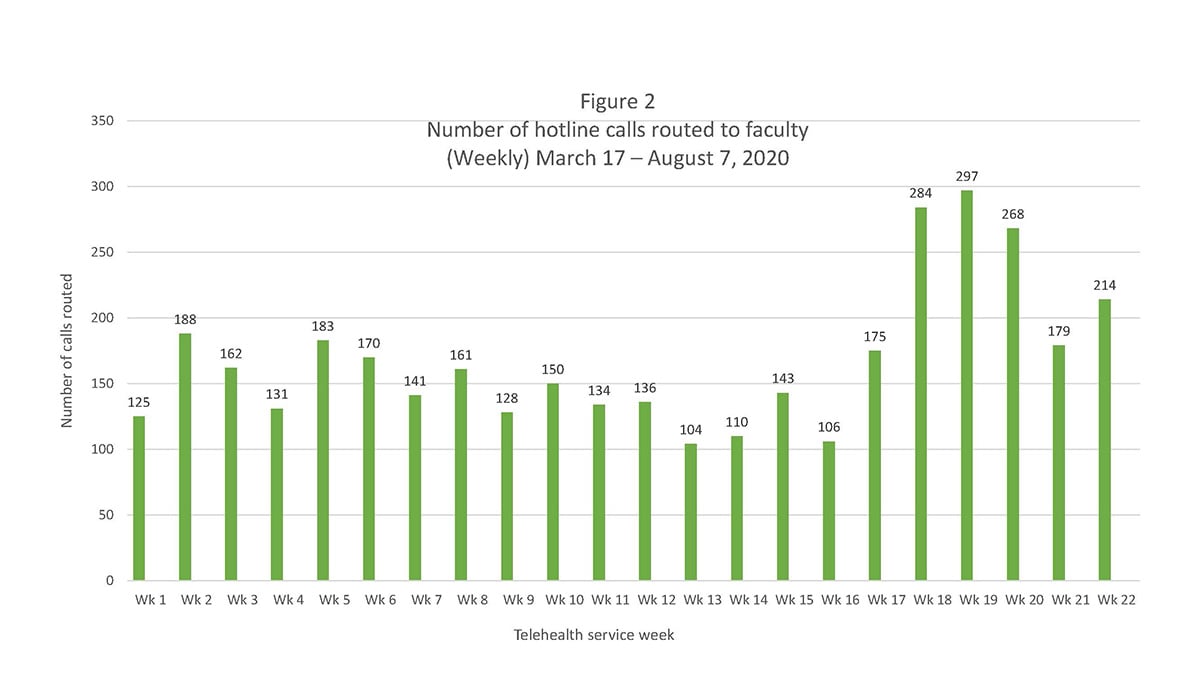

Telehealth Service performance metrics. Hotline callers with an urgent care need or dental emergency, were routed to a provider for a Telehealth session. For most of the service period, the number of calls agents routed to providers ranged from 100-200 calls weekly. As the phased re-opening of NYU Dentistry’s Urgent Care and Specialty Practices occurred, Telehealth hotline calls surged and the volume of calls routed to providers peaked sharply. Specifically, during the phased re-opening, in weeks 18-20 (July 13th – August 2nd), the number of routed calls approached 300 per week and week 22 (August 9th – 16th) had 200 routed calls (see Figure 2).

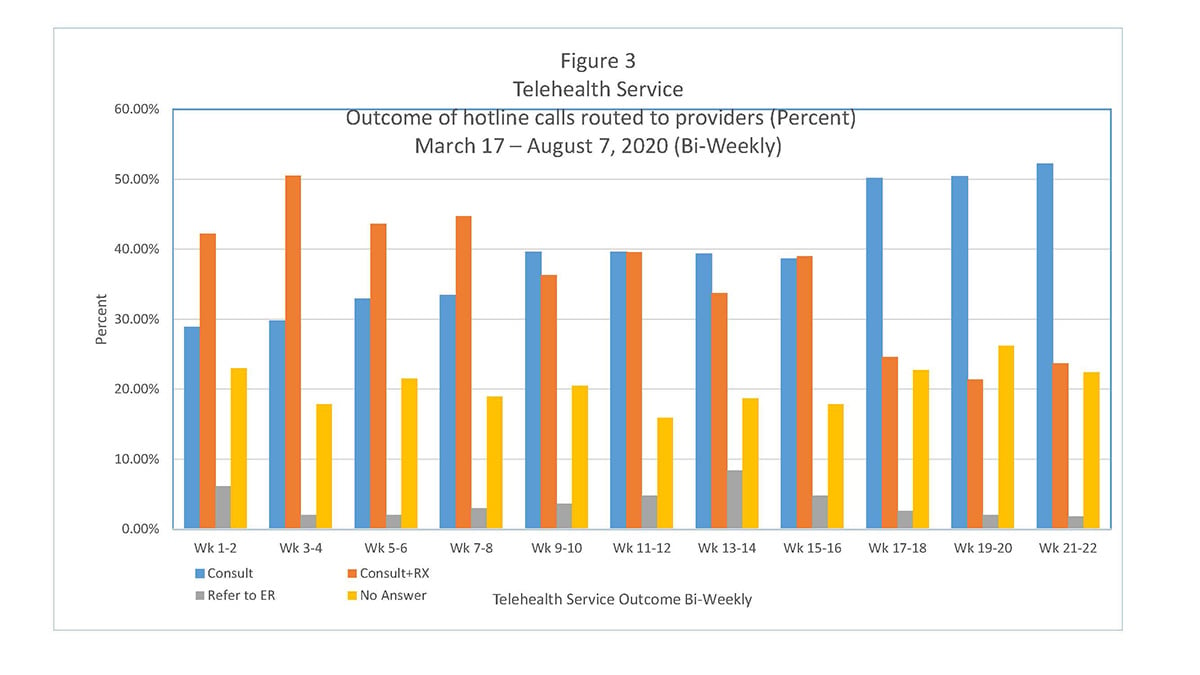

Telehealth Service outcome metrics. Providers had the following dental healthcare management options to offer routed callers during the Telehealth session: a) Consultation with advice/recommendations; b) Consultation with prescription; or, c) Referral to the nearest Emergency Room. The most common management option during the period when services were suspended (weeks 1-15), was “consultation with a prescription.” The second most common management option during this same period was “consultation with advice/recommendations” (i.e., dietary options or restrictions, over-the-counter (OTC) medications and treatments). However, once the phased re-opening of NYU Dentistry’s clinical operations began on June 29th (week 16), the most common management option in the Telehealth sessions going forward was “consultation with a recommendation to a NYU Dentistry clinical service.”

The distribution of these routed calls for emergency/urgent care by management option is shown in Figure 3, organized in two-week service intervals. It merits noting that throughout the 22-week period, when NYU Dentistry’s clinical services were suspended or limited (during the phase-in period), only a relatively small percentage of the Telehealth sessions had “referral to the Emergency Room” as the management option. In any given two-week period, with one exception, less than 5% of these sessions ended in “referral to the ER.” However, just before the phased re-opening of NYU Dentistry’s Urgent Care clinic, 8.4% of the provider sessions held over June 8th – June 21st (weeks 13-14), had “referral to the ER” as the management option (see Figure 3). This increased need for emergency care may reflect a growing unmet need for dental services in the community, given the lengthy period that in-person delivery of clinical care was suspended. It also suggests that NYU Dentistry’s phased re-openings of the Urgent Care Clinic and AHEC service provided timely and needed, emergency and urgent dental care resources.

Concluding thoughts, recommendations and lessons learned

The NYU Dentistry Telehealth Service was established to mitigate the impact of the suspension of oral health services during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. The service was developed to assess and address urgent and emergency oral health issues, and to forestall unnecessary visits to the ER. A review of the Telehealth service outcomes documents that the program achieved these objectives. Callers to the Telehealth hotline were able to receive targeted clinical advice and guidance from providers, as well as, prescriptions, when clinically warranted. Only a small percentage of the Telehealth routed callers were ultimately referred to the ER for care. With the initiation of NYU Dentistry’s Urgent Care and Specialty Practices phased re-opening of service, referral to these services became the treatment of choice. Over time, as clinical operations increased to six days/week, Telehealth session demand decreased.

There were some challenges introducing a dental telehealth service to a community population without a phase-in period. Limitations in the technological resources (i.e., smart phones, notepads or laptops) patients had available to use when on the Telehealth call with the provider restricted access to video connections that would have aided in the diagnosis of the oral health issue. In these instances, through a lengthier discussion and a more probing series of questions to determine the problem, providers were still able to make a diagnosis and develop a treatment plan. An issue that occasionally arose, due to the sheer volume of patients who used the Telehealth hotline, was that, at times there was no “continuity of care” if a patient called back needing additional guidance. Some patients were momentarily disconcerted if they called at a later time to find that their provider contact, with whom they had established a relationship, was not currently available and they now needed to discuss their oral health issue with someone else. However, it merits noting that the Telehealth service had added value, beyond the clinical services that were provided. Although data was not collected on the psychological well-being or program satisfaction of callers to the service, anecdotal reports from the Telehealth providers document that the patients who used the service often expressed feeling relieved and less anxious. Patients also spontaneously shared their gratitude for the advice and assistance received.

Future of Telehealth in dental care

NYU Dentistry implemented extensive infection control safety protocols to safely resume clinical operations, including the re-opening of specialty practices and the delivery of emergency and urgent care. As the phased-in resumption of in-person delivery of clinical care progressed, call volume to the telehealth hotline substantially declined. The Telehealth Service, developed to address the suspension of clinical operations during the surge in COVID-19 cases, was halted. Overall, this service was shown to be a valuable resource when access to dental care is limited and generated a readiness to incorporate it into the continuum of care at NYU Dentistry. Currently, telehealth visits are being used in a few departments for consultations and follow-up care. There is also growing recognition of the benefit of these sessions for intake and screening of new patients. Students are instructed to use the concept of telehealth to contact their patients before a formal appointment to consult on their COVID-19 status, and to upgrade their charts with a review of medical history, thus saving precious "chair time.”

In mid-December 2020, NYS Governor Andrew Cuomo signed legislation requiring dental telehealth services to adhere to the same standards of appropriate patient care required of any other dental health service12. While this amendment protects dental patients, issuing it at this point in time is clearly a recognition of the potential value of dental telehealth in the delivery of dental care and the likelihood of it becoming an established dental care modality.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2000) Summary of CDC COVID-19 Guidance for Dental Services. Updated December 1, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/statement-COVID.html Accessed 12/11/2020.

- American Dental Association. (2020). Return to Work Interim Guidance Toolkit. Available at: https://success.ada.org/en/practice-management/patients/infectious-diseases-2019-novel-coronavirus. Accessed 12/11/2020.

- Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist, Lofy KH, Wiesman J, et al. (2020) “First Case of 2019 Novel Coronavirus in the United States.” New England Journal of Medicine; 382:929-36. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191

- Thompson CN, Baumgartner J, Pichardo C, et al. (2020) “COVID-19 Outbreak — New York City, February 29–June 1, 2020.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 69:1725–1729. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6946a2external icon. Accessed 12/11/2020.

- Executive Order No. 202: Declaring a Disaster Emergency in the State of New York. March 7, 2020 | 1:15 PM EST. https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/no-202-declaring-disaster-emergency-state-new-york. Accessed 10/25/2020.

- Governor Cuomo Signs the 'New York State on PAUSE' Executive Order.” March 20, 2020, Albany, New York. https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-signs-new-york-state-pause-executive-order Accessed 10/25/2020.

- Governor Cuomo Issues Guidance on Essential Services Under The ‘New York State on PAUSE’ Executive Order.” March 20, 2020, Albany, New York. https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-issues-guidance-essential-services-under-new-york-state-pause-executive-order Accessed 1/7/2021.

- Cisco Jabber https://www.cisco.com/c/en/us/products/unified-communications/jabber/index.html Accessed 10/25/2020.

- Pearce PF, Ferguson LA, George GS, Langford CA. “The essential SOAP note in an EHR age.” The Nurse Practitioner. (February 18, 2016), 41(2): 29-36. doi: 10.1097/01.NPR.0000476377.35114.d7

- Moore PA, Ziegler KM, Lipman RD, Aminoshariae A, Carrasco-Labra A, Mariotti A. “Benefits and harms associated with analgesic medications used in the management of acute dental pain: An overview of systematic reviews.” JADA (The Journal of the American Dental Association). 149(4): P256-265.e3, April 01, 2018. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2018.02.012

- Lockhart PB, Tampi MP, Abt E, …Urquhart O, O’Brien KK, Carrasco-Labra A. “Evidence-based clinical practice guideline on antibiotic use for the urgent management of pulpal- and periapical-related dental pain and intraoral swelling.” JADA (The Journal of the American Dental Association). November 2019, p906-921.e12

- https://www.assembly.state.ny.us/leg/?default_fld=&leg_video=&bn=A10034&term=&Text=Y Accessed 12/17/2020.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The COVID-19 emergency Telehealth Program service would not have been possible without the combined effort of numerous NYU Dentistry faculty, residents, administrators, and service teams. We want to acknowledge the contributions of these dedicated individuals and teams (listed below), who generously devoted their time and expertise to attend to the oral health needs of the community during the unprecedented public health crisis that the COVID-19 pandemic precipitated. We are grateful to the following NYU Dentistry contributors, who demonstrated their dedication to the profession, and their showed their willingness to serve.

ADMINISTRATORS: Robin Elliott, Terry-Ann Brown, Yana Chertok, Gracelyn Harris, Clyde Jackson, Jakai Reid, and Anthony Rice.

FACULTY: Amin Ayoub, William Bongirno, Safdar Chadda, Jesse Dosche, Fred Dubrowsky, Edgard El Chaar, Natasha Elson, Laurie Fleisher, David Glotzer, Kim Goldman, Leila Jahangiri, Dominique Juste, , Ross Kerr, Douglas King, William Konicki, Alexander Lezhansky, Arnold Liebman, Katayoon (Kathy) Noorzi Liebowitz, Juana Luster, Matthew Malek, Asma Muzafar, Peter Mychajliw, Olivier Nicolay, Asgeir Sigurdsson Chrystalla Orthodoxou, Kay Oen, Jaclyn Park, Arnold Pollikoff, George Raymond, Maria Rodriguez, Raid Sadda, Asgeir Sigurdsson, Huzefa Talib, James Uyanik, June Weiss, All Faculty and Residents of the Orthodontics Department and All Faculty and Residents of the Pedodontics Department.

AGENTS: Jessica Carrillo, Sat E., Ricardo Fernandez, Monique Henry, Katherine Ramirez, Patricia Salas, and Lena Tsui.

NYU DENTISTRY TEAMS: Clinical Affairs, Clinic Operations, Communications, Compliance and Emergency Response, EHR, and IT Operations

__________

Dr. Victoria H. Raveis

Research Professor and Director

Psychosocial Research Unit on Health, Aging and the Community

Department of Cariology & Comprehensive Care

College of Dentistry

Co-Director, Aging Incubator, Office of the Provost

Affiliated Faculty, School of Public Health

New York University

Email: victoria.raveis@nyu.edu

Dr. David L. Glotzer

Clinical Professor

Department of Cariology & Comprehensive Care

College of Dentistry

New York University

Email: david.glotzer@nyu.edu

Dr. André V. Ritter

Professor and Chair

Department of Cariology & Comprehensive Care

College of Dentistry

New York University

Email: andre.ritter@nyu.edu