The Early Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Emergency Department Visits for Dental Problems – Dr. Lisa Simon, Dr. Regan H. Marsh, Dr. Margaret Samuels-Kalow

Abstract

Background: Dental problems are a common cause of potentially preventable visits to the emergency department (ED), largely due to challenges accessing dental care for many vulnerable individuals. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated closure of dental practices on rates of ED visits for dental problems at two large tertiary care hospitals in a major Northeastern city.

Methods: This was a retrospective study of all individuals who visited the ED for a dental problem. Patient demographics and daily visit counts were compared across two periods: February 1, 2019 through March 16, 2020, and March 17, 2020 through April 30, 2020 (the period during which all dental practices in the state closed to non-emergencies and a stay-at-home order was made).

Results: There were a total of 1939 ED visits by 1516 individuals during this period. Median daily visits dropped from 5 per day (interquartile range 3-6) to 2 per day from the period between March 16 to April 30 (interquartile range 2-3). Patients who visited the ED for dental problems during the COVID-19 pandemic had higher rates of Medicaid enrollment or uninsurance.

Conclusions: In spite of lack of access to routine dental care, rates of ED use for dental problems declined during the early period of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Practical Implications: Dentists in various phases of reopening their practices may find higher levels of dental need among patients who did not access care either at dental offices or at the ED.

Key Words: Access to care; emergency services/emergency treatment; epidemiology; coronavirus; unmet dental needs

Introduction

Due to differences in insurance coverage and care delivery, access to oral healthcare is an ongoing challenge for many in the United States. When patients who cannot afford or access a dentist experience tooth pain or other acute dental problems, they are often forced to seek care in the emergency department (ED).1 Although such visits make up more than 1.5% of all ED visits annually, comprehensive dental care is almost never available in the ED and treatment is most commonly palliation through an antibiotic prescription and a recommendation to visit a dentist.2

On February 1, 2020, the state of Massachusetts reported its first confirmed case of the novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). On March 10, Governor Charlie Baker declared a State of Emergency, with 100 confirmed cases reported two days later. On March 17, the Massachusetts Dental Society and Massachusetts Department of Public Health provided guidance to all dentists in the state to close their practice to all but emergency management for patients of record.

Like many other ambulatory specialties during the pandemic, dentistry has made some transition to telehealth to meet ongoing need. In March, the federal Office of Civil Rights loosened regulations within the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) to allow providers to use consumer-accessible video chat platforms to conduct telehealth visits during the pandemic.3 However, there are currently only six Current Dental Terminology (CDT) codes that can be billed via telehealth.3 Such codes apply only to triage of dental problems and are not reimbursed by all payers.4 Ultimately, interventional treatment for acute dental problems (e.g. tooth extraction) still requires an in-person visit, which cannot be offered even by practices that are “open” for telehealth.5

Survey results from Massachusetts dentists indicated that 80% were providing some form emergency care either through telehealth or in-person, and 18% were fully closed.6 High reported rates of insufficient PPE and furloughing of staff further demonstrate dramatically reduced capacity for even emergency dental treatment.7 On June 8, Massachusetts entered Phase II of its re-opening plan, which allows for resumption of dental hygiene visits and elective dental care with significantly increased infection control and PPE restrictions.8

Preliminary evidence suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has led to decreased utilization of medical care or delayed presentation to care for acute illness.9,10 However, it is unknown how this could impact care seeking for dental problems when routine dental care is largely unavailable. The purpose of this study was to describe the change in the number of ED visits for dental problems at two large hospitals in Boston, Massachusetts during the first weeks of COVID-19-related “stay-at-home” orders and dental practice closures.

Methods

This was a retrospective analysis of electronic health record data from patients who visited the EDs of two large tertiary care facilities located in Boston, Massachusetts.

Patients were included if they were over age 18 and made a visit to the ED between February 1, 2019 and April 30, 2020 with at least one International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th edition (ICD10) code for an ambulatory-sensitive dental condition (A69.0, K02, K03, K04, K05, K06, K08, K09.8, K09.9, K12, and K13). Human subjects review board approval was obtained (Partners IRB# 2020P001142).

Date of visit and total visits per day were recorded. Demographic information was collected, including gender, age at presentation, insurance enrollment, race/ethnicity, and preferred language. Other chronic diagnoses, based on ICD9 or ICD10 code were recorded.

Descriptive statistics were calculated. Whether or not patients had diabetes, hypertension, or a substance use disorder (SUD) was identified based on whether a patient’s problem list included at least one ICD9 or ICD10 code for these conditions as defined by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Clinical Classifications Software.11,12 ICD10 codes for SUD included F10-F16, F18, and F19; individuals coded as having tobacco use disorder were not included. We divided insurance status by whether individuals had Medicaid, Medicare, private insurance, or were considered to be self-pay/uninsured. We also noted whether individuals were dual eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid. We divided visits into two time periods: February 1, 2019 until March 16, 2020, and March 17, 2020 through April 30, 2020, the most recent day for which visit data was available. Differences in patient demographics were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum tests for patient age, gender, prevalence of comorbidities, and insurance enrollment. Differences in categorical variables were evaluated using X2 chi-squared tests. Because visit count data was not normally distributed, differences in median daily visits were evaluated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. All statistics were calculated using Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp; College Station, Texas).

Results

Characteristics of Study Subjects

From February 1, 2019 to April 30, 2020, there were a total of 1939 ED visits resulting in a dental diagnosis, made by 1516 individual patients. Of these patients, 779 were female and 737 were male (51.4% and 48.6%, respectively). The average age was 44.4±17.8 years (range 18 to 94 years). Most patients identified as white (793 patients, 52.3%), followed by Black (325 patients, 21.4%), Latinx (92 patients, 6.2%), and Asian (65 patients, 4.3%). The most commonly spoken language was English (1300 patients, 85.8%), followed by Spanish (120 patients, 7.9%) and Arabic (28 patients, 1.9%). A total of 521 patients (34.4%) had hypertension, 210 (13.9%) had diabetes, and 370 (24.4%) had a substance use disorder (SUD).

Main Results

Patient demographics before and after practices closed are displayed in Table 1. There were 1840 total visits by 1265 unique patients from February 1, 2019 through March 16, 2020, and 99 visits by 67 unique patients from March 17, 2020 through April 30, 2020. There was no significant difference in age, gender, race/ethnicity, or language when comparing visits from before and after closure of dental practices. However, patients were significantly more likely to be Medicaid beneficiaries (47.8% during the pandemic versus 33.3% of all patients before the pandemic), dual eligible enrollees of Medicare and Medicaid (16.4% versus 6.3%), or to be uninsured (17.9% versus 9.6%; p values 0.015, 0.001, and 0.03, respectively).

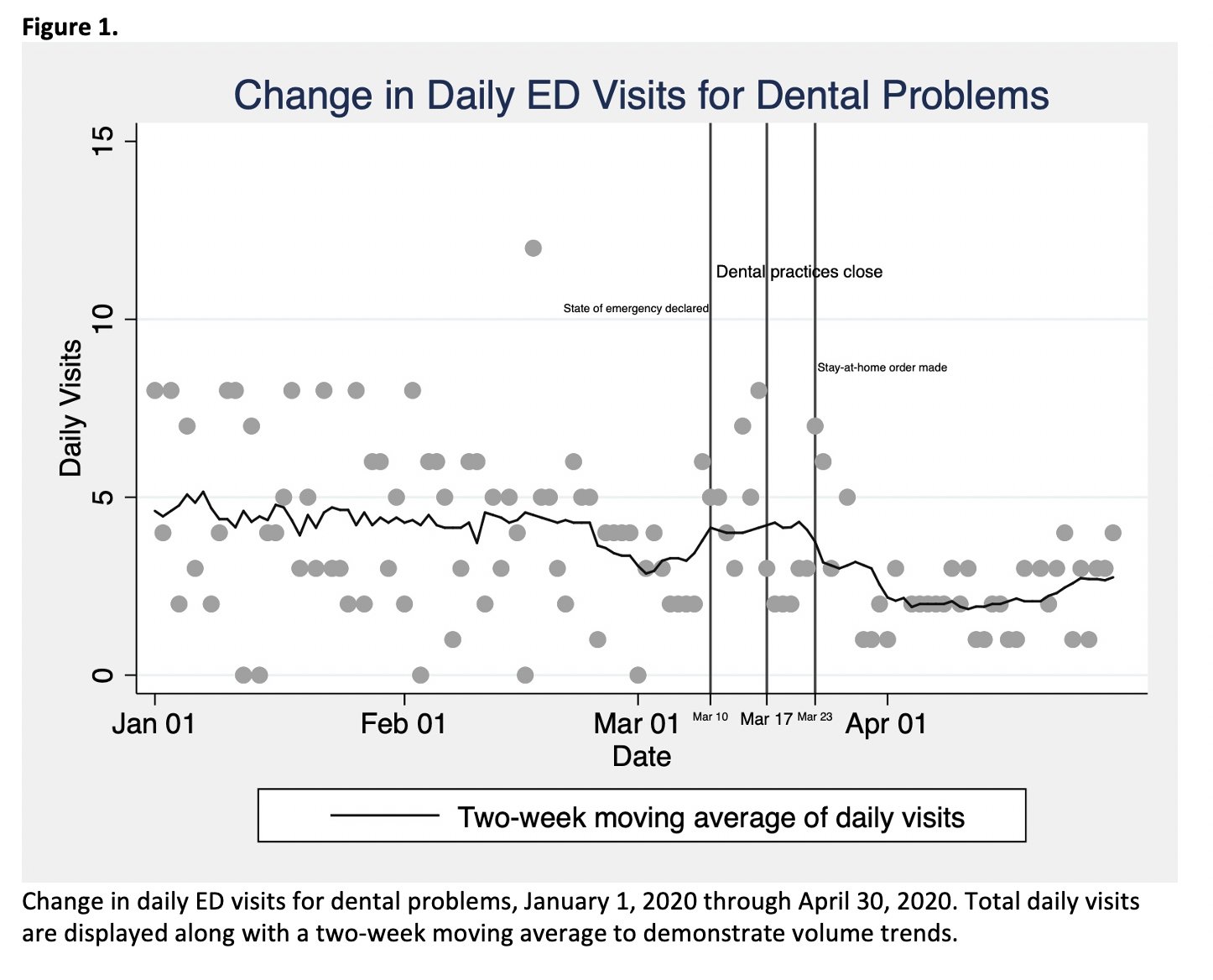

The median number of daily visits was 4 four throughout the pre-pandemic study period (interquartile range 3-6) and dropped to 2 two daily visits (interquartile range 2-3) after dental practices closed on March 17 through April 30 (p<0.001).

Daily visits from January 1, 2020 through March 31, 2020 are plotted in Figure 1. A two-week moving average was superimposed to demonstrate change in average daily ED visits for dental problems over time. Key dates regarding the status of COVID-19 in Boston and its impact on freedom of movement and dental access are labeled.

Discussion

Poor oral health has been associated with worse overall health outcomes, and missing needed dental care can result in health harms, psychological distress, and economic costs to patients.13 While the economic impact of COVID-19 on dental practices nationwide has been well documented,7 the extent to which prolonged closures or reductions in dental practices affected patients is largely unknown. To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating changes in ED visits for dental problems in the United States since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Despite statewide dental practice closures, our results found that patients sought care for dental problems at a lower rate once the COVID-19 pandemic reached Boston. This is consistent with presentations for other chronic and acute health problems,9,10 as well as preliminary findings from other international assessments of emergency dental service utilization, which also found an increase in severity of those that did present for care.14–16

Of those that did present to the ED in our sample, there were no significant differences in most patient demographics, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, and primary language. Of the 99 visits ED visits for a dental problem from March 16 to April 30, 23 were made by patients who had already visited the ED at least once for a dental problem in the same time frame. This suggests that patients who may usually receive dental care elsewhere are not yet turning to the ED for care.

Our study did find that individuals who presented to the ED for a dental problem during the COVID-19 pandemic were more likely to be Medicaid beneficiaries or be uninsured than those visiting prior to the pandemic. Such patients are less likely to have a dental home;17 given that many dentists reported providing emergency care only to patients of record,18 this may have had a disproportionate impact on patients with risk factors inhibiting dental access prior to the pandemic. While federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) have reported higher patient volumes than private practices throughout the pandemic, many dental staff in FQHCs have been redistributed to frontline roles such as administering COVID-19 testing to patients.19 Even with a less sharp reduction in patient volume than the private practice sector, FQHCs, which historically care for a population with higher rates of unmet dental need and a greater number of acute dental issues, may have been unable to accommodate demand during the pandemic, prompting patients to seek ED care.

It is also possible that later ED utilization patterns for dental problems will change, as the length of time since individuals were able to access routine dental treatment grows longer, and as public perceptions of nosocomial COVID-19 transmission evolves. Such a pattern of initial decline followed by a surge in visits for potentially preventable needs has been described after natural disasters.20 Periods of economic downturn, with subsequent loss of dental coverage, have also resulted in higher rates of ED utilization for dental problems.21 The rapid increase in pandemic-related unemployment, with related loss of dental insurance benefits or disposable income to spend on dental care, may result in similar changes in utilization independently of whether or not dental practices are open.

While dental practices nationwide were closed from March 23, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provided guidance to do so, by the end of May, 90% of dental practices nationwide had begun to reopen.22 Nonetheless, the volume of patient care provided remains substantially reduced, especially in light of reported PPE shortages and the need for longer patient appointments to facilitate surface decontamination as recommended by the CDC.6,23 As dental practice resumes, it is unknown how changes in infection control practices, workflow, and practice costs will impact patient dental outcomes.24

The evolution of dental practice in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic may have distinct considerations for the patients without routine access to dental care who are more likely to present to the ED with a dental problem. For example, “infection control fees” that reflect that higher costs of adequate PPE may be more likely to deter patients with limited means.25 Similarly, Medicaid-accepting practices that operate on slimmer margins may be unable to remain viable without additional funding such as that being provided by some private dental insurers.26

This study has a number of limitations. As this is an observational study, we cannot infer the causes behind changes in care seeking patterns. While Medicaid in Massachusetts provides comprehensive dental benefits for adults, we cannot infer whether individuals had dental insurance based on their medical insurance enrollment. We did not evaluate the severity of patient presentation. Because we only examined patterns within our institution, we cannot conclude whether patients are seeking dental care at elevated rates at other EDs. The overall rate of ED utilization for dental problems in our ED is lower than the national average, which potentially calls into question the generalizability of our findings. However, as an early center of COVID-19 spread and mitigation policy implementation in the US, our results may be indicative of predicted patterns of service use in communities with more delayed community spread of the virus.

Conclusions

Our preliminary study of visits to the ED for dental problems during the first weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic found substantially decreased visit numbers despite closure of dental practices across the state. Patients who did visit the ED for a dental problem during this time had similar demographic characteristics to those who visited the ED before COVID-19 was recognized in Massachusetts. Ongoing surveillance as the length of time without dental access grows may provide additional insight into the implication of the pandemic on ED utilization for this and other potentially preventable problems. Such data can play an important role in understanding patterns of health system utilization and anticipated future need for a common and costly ED presentation.

References

- Allareddy V, Rampa S, Lee MK, Allareddy V, Nalliah RP. Hospital-based emergency department visits involving dental conditions: profile and predictors of poor outcomes and resource utilization. JADA (1939). 2014;145(4):331-337. doi:10.14219/jada.2014.7

- Kelekar U, Naavaal S. Dental visits and associated emergency department–charges in the United States: Nationwide Emergency Department Sample, 2014. JADA. 2019;150(4):305-312.e1. doi:10.1016/J.ADAJ.2018.11.021

- United States Department of Health and Human Services O of CR. OCR Announces Notification of Enforcement Discretion for Telehealth Remote Communications During the COVID-19 Nationwide Public Health Emergency | HHS.gov. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2020/03/17/ocr-announces-notification-of-enforcement-discretion-for-telehealth-remote-communications-during-the-covid-19.html. Accessed April 8, 2020.

- American Dental Association. COVID-19 Coding and Billing Interim Guidance.; 2020.

- Daniel SJ, Kumar S. Teledentistry: a key component in access to care. The journal of evidence-based dental practice. 2014;14 Suppl:201-208. doi:10.1016/j.jebdp.2014.02.008

- ADA Health Policy Institute. COVID-19 Panel full summary report April 20 | Reports. https://surveys.ada.org/reports/RC/public/YWRhc3VydmV5cy01ZTlkYjFlMTRlZDkxOTAwMTU4NTU4ZmItVVJfNWlJWDFFU01IdmNDUlVO. Published April 20, 2020. Accessed May 15, 2020.

- Carey M. Fourth wave of HPI polling shows dental practices in early stages of recovery. ADA News. https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2020-archive/may/fourth-wave-of-hpi-polling-shows-dental-practices-in-early-stages-of-recovery?&utm_source=cpsorg&utm_medium=covid-main-lp&utm_content=cv-hpi-view-poll-results&utm_campaign=covid-19. Published May 11, 2020. Accessed May 23, 2020.

- Massachusetts Dental Society. Phase 2. MDS Member Resources, Coronavirus. https://www.massdental.org/Member-Resources/Practice-Management/Coronavirus/Phase-2. Published June 6, 2020. Accessed June 8, 2020.

- Solomon MD, McNulty EJ, Rana JS, et al. The Covid-19 Pandemic and the Incidence of Acute Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. May 2020:NEJMc2015630. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2015630

- Baum A, Schwartz MD. Admissions to Veterans Affairs Hospitals for Emergency Conditions During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA. June 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.9972

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). HCUP Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Published 2009. Accessed June 8, 2020.

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) for ICD-10-PCS (beta version). https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs10/ccs10.jsp. Published 2020. Accessed June 8, 2020.

- Murthy VH. Oral Health in America, 2000 to Present: Progress made, but Challenges Remain. Public Health Reports. 2016;131(2):224-225.

- Long L, Corsar K. The COVID-19 effect: number of patients presenting to The Mid Yorkshire Hospitals OMFS team with dental infections before and during The COVID-19 outbreak. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. May 2020. doi:10.1016/j.bjoms.2020.04.030

- Guo H, Zhou Y, Liu X, Tan J. The impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on the utilization of emergency dental services. Journal of Dental Sciences. March 2020. doi:10.1016/j.jds.2020.02.002

- Yu J, Zhang T, Zhao D, Haapasalo M, Shen Y. Characteristics of Endodontic Emergencies during COVID-19 Outbreak in Wuhan. Journal of Endodontics. April 2020. doi:10.1016/j.joen.2020.04.001

- Baicker K, Allen HL, Wright BJ, Taubman SL, Finkelstein AN. The Effect of Medicaid on Dental Care of Poor Adults: Evidence from the Oregon Health Insurance Experiment. Health Services Research. September 2017. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12757

- Carey M. Second week of HPI polling shows dentists’ response to COVID-19. https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2020-archive/april/second-week-of-hpi-polling-shows-dentists-response-to-covid-19. Published April 10, 2020. Accessed April 16, 2020.

- ADA Health Policy Institute. COVID-19: Economic Impact on Public Health Dental Programs (Summary Report). Chicago; 2020.

- Malik S, Lee DC, Doran KM, et al. Vulnerability of Older Adults in Disasters: Emergency Department Utilization by Geriatric Patients after Hurricane Sandy. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness. 2018;12(2):184-193. doi:10.1017/dmp.2017.44

- Neely M, Jones JA, Rich S, Gutierrez LS, Mehra P. Effects of cuts in Medicaid on dental-related visits and costs at a safety-net hospital. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6):e13-6. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.301903

- ADA Health Policy Institute. COVID-19 Panel Full Summary Report June 1. Chicago; 2020.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Guidance for Providing Dental Care During COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/infectioncontrol/statement-COVID.html. Published April 20, 2020. Accessed April 8, 2020.

- Simon L. How Will Dentistry Respond to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic? JAMA Health Forum. 2020;1(5):e200625-e200625. doi:10.1001/JAMAHEALTHFORUM.2020.0625

- Galewitz P. Open (Your Wallet) Wide: Dentists Charge Extra For Infection Control | Kaiser Health News. Kaiser Health News. https://khn.org/news/open-your-wallet-wide-dentists-charge-extra-for-infection-control/?utm_campaign=KHN%3A Daily Health Policy Report&utm_medium=email&_hsmi=88910015&_hsenc=p2ANqtz--WvWEj-9G67rbKJQeIS019DzNvVZq-WbPCNJTySuyyAOPw-XbSuZzZW8zfBidLVMz3fNILPf52wvexjejrIk4pqyiH1iFRRnJq7OYF7T6Y23XC6xI&utm_content=88910015&utm_source=hs_email. Published June 3, 2020. Accessed June 8, 2020.

- American Dental Association. COVID-19 Coding and Billing Interim Guidance: PPE.; 2020.

This submission is included in the JADA+ COVID-19 monograph as a Clinical Observation entry and has not been peer reviewed.

Stock photo credit: sshepard/E+/Getty Images